Supply Chain Transparency in Fashion

A few weeks ago, the Guardian broke a story about the realities behind the Spice Girls T-shirts being sold in support of Comic Relief. The tees intended to raise money for Comic Relief’s ‘gender justice’ campaign were manufactured by women in Bangladesh earning less than 35p per hour. Not only that, but these women are regularly required to work 16-hour shifts where bullying and harassment are the norm. Irony doesn’t begin to cover it.

While it’s easy to point fingers and debate how this might have happened, the complexities behind it are not so easy to unwind. And that’s because trying to trace supply chains in apparel manufacturing is rarely straightforward. According to the article, the Spice Girls commissioned Represent to make their t-shirts, and Comic Relief vetted them and their manufacturing processes. So far, so good. But then Represent switched suppliers, to Stanley/Stella, without informing Comic Relief. They, in turn, had the t-shirts manufactured by Interstoff Apparels in Bangladesh where the women were mistreated and underpaid (although they deny the allegations).

Switching suppliers and/or outsourcing are very common practices within the industry, especially when brands are chasing cheap retail price points. Actually, the fact that only 3 – 4 organisations were involved in this particular case demonstrates a fairly simple supply chain. I have been cited many examples of High Street brands being unable to accurately trace their own suppliers because of outsourcing. While they make an agreement with one supplier, that supplier may outsource to another, and so on and so forth. At the end of the day, it is often impossible to know exactly who made the clothes, let alone the circumstances in which they were manufactured.

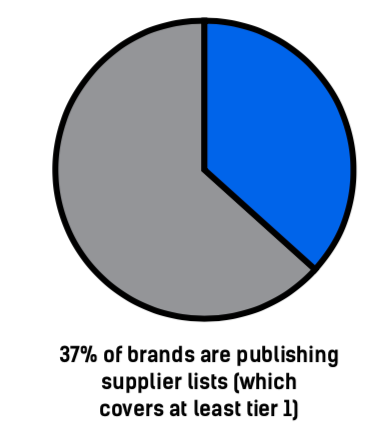

This situation is compounded by the fact that many brands do not even disclose their ‘tier one suppliers’ – the company that they contract with initially to produce their clothing. There are some fantastic organisations shining a light on this situation, including Fashion Revolution. Each year, it produces a Transparency Index, reviewing 100 major fashion brands and their practices. Their review in 2018 showed that the industry, while improving, still has a long way to go. Only 37% of brands share their Tier One supplier lists. The good news is that this is up from 32% in 2017. However, it means that 63% of brands do not share any information about suppliers, let alone who those suppliers may subcontract to fulfil the order and meet pricing targets.

However, there are some very positive developments that lead me to believe transparency in the industry will accelerate and will be aided by technology. Already, the company Provenance is using its digital platform to partner with apparel and accessories brands to trace their products all the way back to the raw material stage. This is a platform powered by blockchain, and I believe that it will become the norm in fashion. We take for granted that when we buy any produce from the supermarket, its label will show where it was grown, and often the name of the farmer who grew it. Why should it be any different for clothing?

However, there are some very positive developments that lead me to believe transparency in the industry will accelerate and will be aided by technology. Already, the company Provenance is using its digital platform to partner with apparel and accessories brands to trace their products all the way back to the raw material stage. This is a platform powered by blockchain, and I believe that it will become the norm in fashion. We take for granted that when we buy any produce from the supermarket, its label will show where it was grown, and often the name of the farmer who grew it. Why should it be any different for clothing?

And so, the second wave of digital disruption is coming to fashion. The movement to online shopping was, of course, the first, and I believe there will be some important parallels between the two. The rise and success of the big e-commerce players (Net-a-Porter, ASOS) were driven by those brands abilities to build an end-to-end online business from scratch. Bricks and Mortar retailers were simply not setup to serve online customers, either from an inventory holding or customer service standpoint, and therefore took years to establish themselves in this space, by which point they had ceded the market to those early upstarts. It will be the same for transparency. While huge high street brands work to untangle their messy supply chain webs, small, nimble brands will be able to take the lead in this space. Like those early e-commerce players, they will be building their businesses the right way from the very beginning.

It’s something to consider when choosing where to spend your money as a consumer. It might seem that you are being ‘safe’ by purchasing from a well-established brand, rather than a small, new brand -- one that perhaps you have not heard of before. But it is the small brand that, more often than not, will be able to tell you about who made your clothes, and how. These are the brands establishing direct and personal relationships with their manufacturing partners. In my opinion, they are the safest option of all.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Instagram

Instagram